NEW YORK — Few American politicians have embraced the role of public health ambassador as comfortably as Mike Bloomberg, who banned smoking in bars and restaurants, outlawed trans fats and unsuccessfully pushed to restrict soda size.

The former New York City mayor was so content in that role, he once performed in a charity show as Mary Poppins to spoof his “nanny” persona.

Now, New Yorkers have chosen another wellness zealot, following eight years of a mayor who largely avoided the thorny intersection of health mandates and personal choice until confronted with the Covid-19 pandemic.

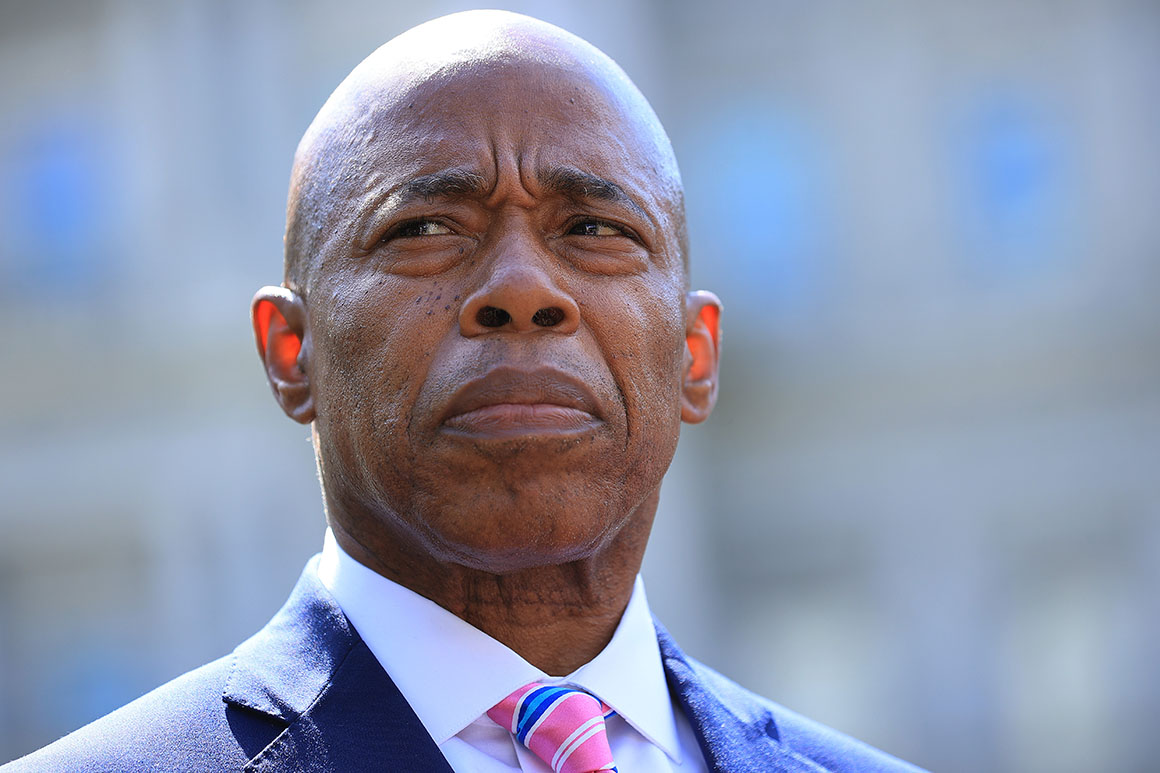

Mayor-elect Eric Adams, a former NYPD captain, traded jelly doughnuts for kale smoothies when diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes five years ago. Since then, he reversed vision loss and nerve damage, shed 35 pounds and anointed himself a spokesperson for a plant-based lifestyle. As he prepares to take over City Hall, a job that comes with a national bully pulpit, he stands to turn his passion into policy.

“We can save more lives with plant-based diet if people would only realize they are enslaved to fats, oil, sugar and things that are killing their body,” Adams said in a short 2018 film produced by Forks Over Knives, a company that promotes a whole-foods diet.

In electing Adams — a fit 61-year-old who once boasted, “I don’t have a six-pack, I have a case” — voters have chosen someone who used his public perch as Brooklyn borough president to proselytize a vegan diet. He showed off his intricate smoothie recipe and office-based stepper for TV cameras, spearheaded a plant-based diet program at a leading city hospital and authored “Healthy At Last” — part memoir, part cookbook intended to overhaul the diets of its readers. (Even olive oil, dubbed “liquid fat,” didn’t escape Adams’ scorn.)

Adams, a Democrat, brought his devotion to the mayoral campaign trail — vowing to fund doulas for pregnant women because “the first classroom is in a mother’s womb,” meditating on stage before televised debates and sharing his Election Night victory stage with a doctor who specializes in past life regression and reiki.

Much of the time the incoming mayor, who is Black, focuses on racial disparities in medicine. He likened soul food to “slave food” on a recent podcast and pledged to build clinics in low-income neighborhoods that lack access to top-tier hospitals. And, reasoning that poverty exacerbates health problems, he wants public hospitals to double as hubs for social services, according to campaign literature.

He also promised to clean up city-funded food: No more processed school lunches, sugary drinks for public hospital patients or junk food for detainees in city jails, he told POLITICO in an interview last year.

“You should not be leaving jail unhealthy,” he said. “You should not be in a homeless shelter where I am feeding you on taxpayers’ dime and I am feeding you food like chicken nuggets.”

Adams declined to be interviewed for this story. Asked for further details about his plans to overhaul taxpayer-funded meals, adviser Evan Thies replied: “The mayor-elect will make it his mission to change the dietary paradigm in these facilities, introducing plant-based meals to improve health outcomes and ensure all agencies are aligned on the goal of creating a healthier, more prosperous city for all residents.”

During a recent podcast focused on diet, the incoming mayor said he hopes to grow tomatoes year-round for public schools through vertical farming.

At times, Adams’ dedication morphs into fanaticism: He argued a healthy diet could prevent schizophrenia during a mayoral forum last year and has compared fried food to cocaine and heroin.

A City Council member who declined to be named attributed Adams’ beliefs to “the fervor of a convert.”

In his book, Adams points to research concluding meat, eggs and dairy food increase a child’s risk of asthma, while antioxidants in fruits and vegetables limit that danger.

“This is quite misleading. None of these foods are proven to cause asthma,” said Anna Nowak-Węgrzyn, director of the Pediatric Allergy Program at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone. “It’s oversimplifying a complex matter. It’s important for kids, especially from underprivileged populations, to get a healthy diet, but in terms of asthma we can’t say it can prevent or improve asthma.”

Two former officials in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s health department — both of whom asked for anonymity to speak freely about the incoming mayor — raised concerns that he does not always back up his claims with scientific research, even as they generally agree with his views on nutrition.

“Given the current climate — all the mistrust that has existed and reinforced under the Trump administration — it’s more important to provide more information that’s sound and accurate,” one of the people said. “Obviously he can’t be there speaking off the top of his head.”

During a candidate forum focused on mental health last year, he said scientific research demonstrates that consuming healthy food “can really prevent and treat many of the issues we’re dealing with, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety.”

Shebani Sethi Dalai, founding director of Metabolic Psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine, said even politicians with good intentions should be conscious about spreading misinformation.

“I wouldn’t say these diets could treat bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. There isn’t data to support that,” she said. “I don’t know if it’s responsible … to recommend solely dietary things unless it’s monitored and seeing if it’s working for the individual.”

She also cautioned a vegan diet could result in certain vitamin deficiencies.

In response, Thies pointed to a Harvard Review of Psychiatry study that found “a growing body of literature shows the gut microbiome plays a shaping role in a variety of psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder.”

In his book, Adams also weighed in on an open question about the role of soy — a popular meat alternative — in breast cancer risk, declaring it unequivocally does not contribute to the common disease.

“There’s a myth out there that soy — a common staple of a plant-based diet — can increase breast cancer risk. In fact, the opposite is true,” he wrote, citing the Mayo Clinic. “Even women who have breast cancer can benefit from eating more soy.”

As borough president he championed “meatless Mondays” and pushed to eliminate all processed meat in public schools. He also opened a lactation room in Brooklyn Borough Hall and once proclaimed, “breastfeeding is the best feeding for our youngest Brooklynites.”

Health experts believe Adams’ allegiance to an issue they hold dear — particularly after two terms of a mayor who was at war with his public health agency — will serve the city well.

“He’s got a compelling personal health story, and has highlighted some important means of moving [forward] with plans — understanding that social issues are part of health care, bringing more resources into under-resourced neighborhoods, focusing on prevention. These are really important issues,” said Tom Frieden, former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Bloomberg’s health commissioner.

Yet Adams’ public health plans remain vague.

His campaign book mentions improving access to medical care and enrolling more people in health insurance through “outreach programs” — a tough proposition considering the lack of financial penalty for the uninsured and a dearth of options for undocumented immigrants. To that end, Adams has said he would increase funding for a city program that connects residents to primary care.

Thies also said Adams would look to create a more seamless partnership between public and private hospitals to ease the sharing of data, but did not provide further details on that, or the clinics planned for low-income neighborhoods.

A review of his campaign literature, records as borough president and remarks on the trail hint at Adams’ approach to public health.

For starters, he has asked Mitchell Katz to remain as president and CEO of the public hospital system, three people familiar with the situation told POLITICO. They spoke on condition of anonymity to reveal the internal maneuvering. Katz — who assumed the role in 2018 and has been credited with turning around the beleaguered hospital system’s finances — became one of de Blasio’s most trusted aides during the pandemic, as the mayor sparred with his health commissioner.

A year before launching his mayoral bid, Adams declared he wants every city hospital to open a “lifestyle medicine clinic” to encourage plant-based diets, particularly for patients with diabetes. As borough president in 2018, he spearheaded a similar program within the city-run Bellevue Hospital. Some 300 patients have enrolled so far, with another 850 on a waiting list. The hospital reported participants have experienced weight loss and lowered blood sugar and blood pressure, according to a hospital spokesperson.

He also wants to begin a doula initiative aimed, in part, at advising expectant mothers on nutrition.

“If you do not ensure that that mother has the right nutrition while she is carrying that baby, you can turn on genetic markers that will impact the quality of that child’s life throughout the entire lifespan,” Adams said at a January mayoral primary forum.

He has also expressed interest in revisiting a proposed soda tax, which would require cooperation from state lawmakers and Gov. Kathy Hochul. In his last year in office, Bloomberg pressed for a ban on the sale of sugary drinks that exceeded 16 ounces. The beverage industry immediately sued, and a judge ruled such an edict could only be enacted legislatively. A subsequent soda tax bill is stuck in committee in the state Legislature.

When he assumes office Jan. 1, Adams will face a city struggling with its worst mass-casualty event since the AIDS epidemic. He has hesitated to say much about his plans around Covid-19, but his convictions about diet and exercise are not matched when it comes to the controversial matter of vaccine mandates.

He has repeatedly said he supports the requirements de Blasio recently instituted, while dodging questions on enforcement.

During the final days of the election, he offered oblique solutions, like extended talks with union leaders. Thies said Adams would “enact and enforce mandates according to science, efficacy and the advice of public health professionals” but declined to elaborate. Those professionals urged City Hall to enact a vaccine mandate for municipal workers, and early evidence shows it’s working.

In recent weeks — with more municipal employees getting vaccinated as de Blasio’s threat of lost pay looms as a penalty for those who defy his mandate — Adams and his closest advisers have expressed some concern about the regulation, according to two people who have spoken with them privately.

“My sense is he will have a different approach as de Blasio had,” Henry Garrido — executive director of the city’s largest municipal union, DC37 — said after a recent talk with Adams on the city’s vaccine mandate. Garrido was one of Adams’ earlier endorsers.

“Those who have legitimate reasons for not taking the vaccine, we understand that,” Adams said on MSNBC last month. “This is a city and a country where religion is important. But everyone else that is required to take the vaccine, we’re going to be clear and give a great deal of clarity that this is what’s expected of you.”

Policy issues aside, the new mayor has enthused vegans and fitness aficionados alike.

A meatless bodega sandwich has been crafted in his honor. Outgoing Staten Island Borough President Jimmy Oddo — a Republican in line for a potential Adams administration appointment — said Adams inspired him to keep chasing a desired physique. “I texted Eric a few years ago that ‘I can run through a brick wall after listening to you talk about health and wellness,’” Oddo said in an interview.

“Mayor Adams can be a genuine change agent and can be, in my opinion, a national catalyst for change,” Oddo said.

Garrido recalled Adams sending him a copy of “Healthy at Last” after the union leader lamented his own diet. He said he was touched by the gesture and gave “meatless Monday” a try, though some of the suggested recipes seemed daunting.

“They require a lot of time and … access to a lot of ingredients that aren’t always accessible,” Garrido said. “For somebody with a very hectic schedule, preparing couscous salads [that are] going to take me 50 minutes when I’m traveling is difficult.”

“But I still think he’s onto something,” he added.

With all eyes on Adams as he assumes the vast responsibility of overseeing the nation’s largest city, one thing is certain: Public health is likely to be at the forefront of his agenda.

“If Black lives really matter, it’s more than just George Floyd being murdered,” he said on a podcast this year. “It’s the murder that’s taking place every day in our cities that we feed people bad food.”