Sen. Joe Manchin walks to the Senate chamber to vote on Capitol Hill on Tuesday, Sept. 28, 2021.

Swiftwater Students Seed Native Grasses on Cle Elum Ridge

By Tonya Morrey, Outreach and Stewardship Coordinator, Central Cascades

Amongst the spring beauties, glacier lilies, arrow leaf balsam root, and occasional trillium, you cannot deny spring is in full swing on the Cle Elum Ridge. What better way to celebrate than planting native grass seed with local school students?

We gathered with students from Swiftwater Learning Center under a large ponderosa pine and we discussed the purpose of mastication, or using big machinery to chomp up brush and small trees. Mastication is designed to reduce the threat of fire in the forest and improve forest health.

A student loads native grass seeds into a seed disperser. Photo courtesy of Swiftwater Learning Center.

On this beautiful day in May we were planting native grasses to out-compete non-native species that try to fill in after the forest goes through a disturbance like mastication.

Students helped seed native grasses in areas that had been treated with mastication.

After our chat, students partnered up and marched over the slash-covered forest floor with long measuring tapes, flagging, and compasses to mark off 40 x 40-foot plots. Once complete, they exchanged their equipment for a bag of grass seed and a seed disperser. With a few passes through their plot, we planted around 20 pounds per acre.

The Swiftwater students planted about half our seed supply in 1 day of work. Their efficiency doubled the next day and the grass seeding machines got the rest planted in a couple hours! I hope the students will hike or bike the ridge and come back to see how their 13 plots are doing in the future.

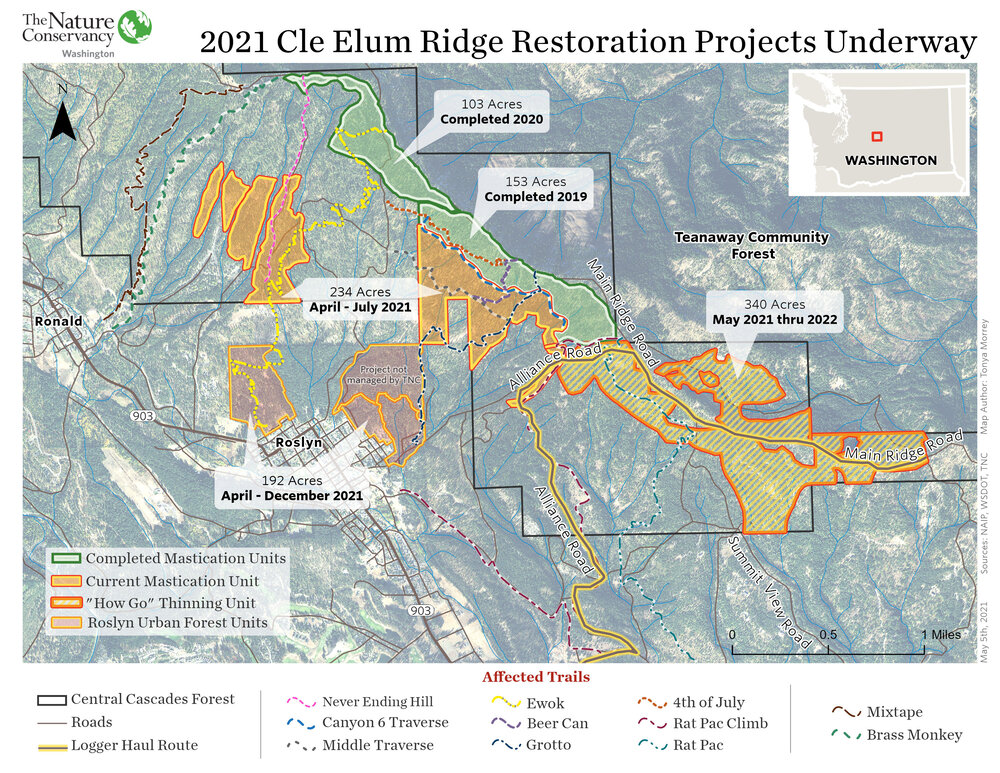

Read more about restoration work on Cle Elum Ridge.

A happy crew after a full day of sowing native grass seeds on Cle Elum Ridge. Photo courtesy of Swiftwater Learning Center.

Banner photo © Tomas Corsini, volunteer photographer.

Potential Impacts of Reopening of the Trawl Rockfish Conservation Area

by Marissa Paulling, graduate student at the University of Washington

In the early part of the new millennium, things were not looking promising for the groundfish fishery of the West Coast. Multiple stocks had been designated overfished, and the Federal Government declared the fishery an economic disaster on Jan. 26, 2000. Too many participants were harvesting too few fish, and the future of sustainable employment for fishermen, many of whom came from coastal communities which depended on fishing, was in question.

>

“I am excited to contribute to knowledge and research being done to address a local conservation challenge, and to support the fishing communities that make up so much of our West Coast fisheries. ”

To address the collapse of the groundfish fishery, catch limits for trips were created, vessel and permit buy-backs programs were created, and the trawl rockfish conservation area (RCA) closed several thousand square miles to bottom-contact gear. The Nature Conservancy played an active role in working with communities and agencies. TNC privately bought out trawl permits, which they later helped redistribute, and worked with fishermen to advance community access to the fishery while advancing technology for conservation use. Much of this work was focused along California’s Central Coast.

Photo: Marissa Paulling, graduate student at the University of Washington

In what many managers and environmentalists are touting as one of conservation’s greatest success stories, the trawl Rockfish Conservation Area (RCA) off the coasts of Oregon and California was reopened on January 1, 2020, as described by Amendment 28 to the West Coast groundfish fisheries management plan.

Spatial closures are a frequently utilized conservation measure, and a growing body of literature describes best practices for managing closed areas or various human behavior responses to closed areas. However, there is a gap in the literature that describes human response to reopened fisheries areas. The reopened trawl RCA provides an important learning opportunity for managers, partners, and fishermen.

Using Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) data, Christina Madonia, Patrick Dodd, and I collaborated with NOAA and TNC to map vessel tracks in response to the reopening of the trawl RCA as part of our graduate research. We wanted to see how fishermen and probable fishing behavior changed between 2015-2020. We were hopeful that the first five years of vessel tracks would inform us of “normal” fishing activity, and that 2020 would exhibit notable differences. We had two hypotheses: the first involved the extent to which fishermen would use these new areas. The second hypothesis was based on our expectation that 2020 would be a year of significantly different fishing behavior.

The Port of Ilwaco, located at the mouth of the Columbia River in Ilwaco, Washington. Photo credit: © Erika Nortemann

The year 2020 was a year unlike any other, and this was representative of our findings of fishing behavior off the West Coast. COVID-19 altered vessel willingness to take an observer. Markets were disrupted, and first receivers tackled Covid outbreaks at their landings. Therefore, only the first quarter of annual fishing data was analyzed. Additionally, we observed a change in ocean productivity, as proxied by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation Index (PDO) over the course of the analysis. But fishermen returned to the reopened RCA, nonetheless.

Of the changes we observed in reopened RCA use, there was a dramatic shift of fishing pressure shoreward. This demonstrates a departure from the trend that many fishermen follow, wherein flatfish and sablefish tend to be offshore in the winter months and migrate onshore during the summer months to spawn. Rockfishes tend to show more site fidelity, not normally engaging in these seasonal onshore-offshore migrations, but rather staying close to home.

The RCA was originally a tool designed to address the overfished status of several rockfish stocks. Six of the seven rockfish stocks that the trawl RCA protected have been rebuilt since the closure, and the last of the stocks is projected to be rebuilt decades ahead of the originally forecast. However, for conservation to be used the best way possible, and to prevent rebuilt stocks from declining, managers must continue with other programs and regulations in place, including a catch shares structure and observer coverage. The Nature Conservancy continues to work closely with several California partnerships to ensure that their livelihoods are sustainable and well managed.

As a student in the Levin Lab at the University of Washington, much of the student work incorporates applying conservation practices within partnerships between shareholders and The Nature Conservancy (TNC). Understanding the history and network that TNC has assisted in creating with fishermen, especially along California’s Central Coast, gives me a great sense of pride. Not only do I trust the seafood options available to me from this region, but as a student of the University of Washington (UW), and with prior field experience with groundfish, I understand the importance of the TNC-UW partnership in fostering conservation focused on the intersection of people and nature.

Learn more about the TNC-UW Partnership

The Nooksack River: Nature of Change

by Carol Macilroy, Floodplains by Design

The long history and more recent series of events that brought us to this point are complicated. Heart-breaking and heart-warming, the history of the Nooksack River and its people shows up today in words said and unsaid, biases known and unknown, relationships formed and unformed, and possibilities for a different future tantalizingly close, but seemingly unattainable.

In the midst of a pandemic and at the start of a potentially divisive water adjudication that was stalling our collaborative work to develop a plan that supported salmon recovery, maintained farm viability and reduced flood risk, a cheery call from Courtney at The Nature Conservancy came. “Do you want to create an animated video to tell the story of the Nooksack floodplain and the effort to bridge across salmon, farms and flood management to shape a better future?” No one was in the mood. No one thought it would be useful.

But it was.

People skipped out of meetings to instead review storyboards. They turned around comments on a dime, and smiled enthusiastically about the video as it began to take shape. Our little collaborative planning team, now fighting for survival but on opposite sides in a water adjudication battle, hung together to create something beautiful, something inspiring. Our team did it together.

“Farmers are not caricatures. No Whatcom County farmer dresses like that. The farm buildings don’t look like that. We have cows, not sheep,” said the farm representative. “There need to be trees. Before they were cut, the landscape had trees. Bigger trees, please.

And, by the way, no salmon has striped adipose fins,” said the tribal staff person.

“Rocks that we drop for armoring are angular, you have put river rock in places that should be angular armoring rock. There is no armoring on the inside of a river bend. Our machines no longer dig in the water like that,” said the flood engineer.

With every detail heard and listened to and then redrawn, the actual people and what they care deeply about began to take shape. The history and issues came forward in drawings with beautiful colors of greens, blues, reds and yellows. We all learned things. We all saw new things.

“This is not all the farmers’ fault,” said a tribal staff person and the farm representative on separate calls in the same week.

“We have no fish. We barely have any fishermen left,” said the tribal staff person.

“We are afraid we will lose everything,” said the farm representative.

“We have already lost everything,” said the tribal staff person.

And through working and reworking, drawing and redrawing, a common story of the Nooksack began to take shape. It was told by the river, because in and through the river, our team began to be seen by themselves and each other. And what came forth was resilient and hopeful. Again.