Free community college. Medicare expansion. A wealth tax.

Democrats tore a litany of progressive priorities out of their signature domestic policy bill, but the House left’s leader is still declaring a win.

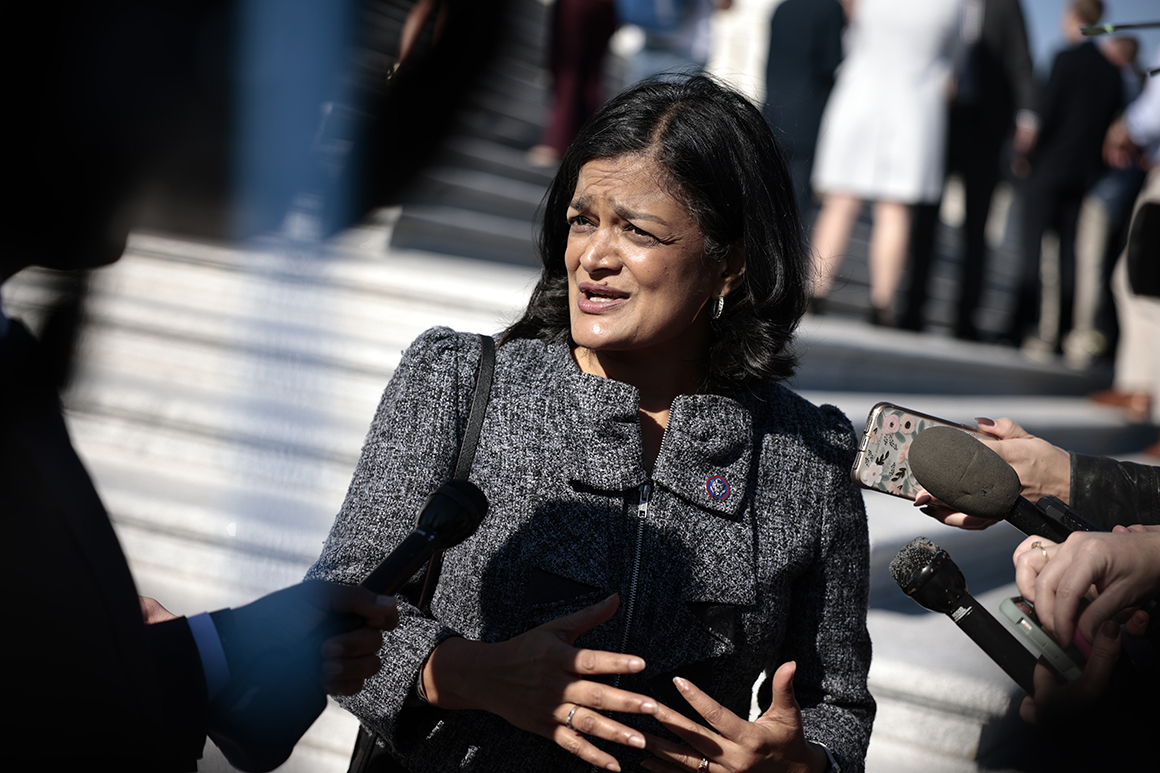

Rep. Pramila Jayapal, who leads the Congressional Progressive Caucus, described the $1.7 trillion social policy bill as just about the best-case scenario, a notable acknowledgment of the microscopic Democratic majorities that have bedeviled liberals all year long. And neither Jayapal nor her members are seriously talking about tanking the Senate’s version of the bill when it comes back to the House for a final green light — if it can get past the further cuts and delays that Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) appears likely to exact.

“What we’re trying to do is make sure it stays as good as possible. We are now counting on the Senate to make sure to preserve it,” Jayapal said in an interview this week.

To be sure, there’s plenty for progressives to like in their party’s bill to expand the social safety net, from universal pre-K to more than $500 billion for climate change. But Jayapal and many in her caucus have spent months fuming as the centrist Manchin threatens to wield a one-man veto pen over their ambitions and push the bill into next year.

And that leaves liberals with the tough task of convincing their restive base that it is, in fact, a victory as attention turns to the midterms.

The sales job is only going to get harder: policies such as paid family leave, immigration, drug price negotiation and subsidized childcare are in jeopardy — facing Manchin’s opposition and the labyrinthine budget rules of the upper chamber. Several senior progressives acknowledged that it would be difficult to communicate liberals’ now-cooperative approach to a broad swath of their voters, who are increasingly restless about inaction in Congress.

“There are a lot of bills that are languishing on the Senate majority leader’s desk because of the filibuster. That’s a very hard thing to explain to people,” said Rep. David Cicilline (D-R.I.). “All they know is we have controlling majorities in all those places, and we ought to be able to deliver, and they’re right.”

Rep. John Yarmuth (D-Ky.), a retiring liberal who’s spent 14 years in the House, chalked up some of the left’s more hardline approach this year to the fact that the House’s newest generation of liberals hadn’t governed in a majority before.

“They were posturing,” Yarmuth said, “but also thinking, ‘maybe I can get 100 percent of what I want.’ Around here if you get 70 percent of what you want, that’s a major victory. I think some of them learned along the way that that’s real life. I think Pramila sure did. But ultimately, she handled it really well and was very effective.”

Indeed, progressives say they’re putting the bill in perspective — as a once-in-a-generation safety net expansion that they fought tooth and nail for, one that still includes some major goals, despite the party’s thin margins. And they say that’ll be the case even if a final agreement leaves out issues such as immigration reform, which the Senate’s parliamentarian has repeatedly rejected under the chamber’s budget rules, or paid leave, a policy that Manchin has said doesn’t belong in the party-line bill.

Yarmuth, the House budget chair, acknowledged his party’s “potential problem”: “We’re not great messengers. But the idea that on the day after the election last year, that we could have done what we’ve done … it’s a miracle,” he said.

Now that the House has passed its version of President Joe Biden’s $1.7 trillion bill, Jayapal wants to focus on what made it in, not what’s out.

“There are always people who are like, ‘you need to do more,’ and it’s true. We do,” Jayapal said. To those who ask why they can’t get more done, given Democrats’ full control of Congress, she replied: “Of course, the answer is, we don’t have enough control.”

But before the House passed its bill, the Washington Democrat took a far different tack, steering her roughly 100-member group through its first real standoff with party leaders over the fate of Biden’s two domestic priorities.

After spending the year consolidating power in her caucus and turning it into a formidable voting bloc, Jayapal and her allies deployed an aggressive strategy that at times alienated her and her members from Democratic party leaders. Progressives singlehandedly — and repeatedly — delayed a vote on an infrastructure bill that some Democrats blamed for confidence-rattling November losses in Virginia, even if some liberals believed it forced senators to take their position seriously.

That progressive House Democrats are not threatening to tank the Senate’s version of the social spending megabill suggests they recognize the limits of their leverage in a divided Congress. The House will need to give final approval before it heads to Biden’s desk, but liberals say they’ve already pushed as far as they can go.

They say it’s now up to Biden to meet his end of the bargain by getting 50 votes in the Senate: “It’s on him to get the job done and make clear that House members’ trust in him wasn’t misplaced,” one senior House aide said, speaking candidly on condition of anonymity.

After a season of intra-party flexes by her bloc, Jayapal also didn’t rule out the possibility of running for leadership in a future Congress.

“I’m always going to be open to whatever is going to help us deliver on the boldest, most transformational agenda, and whatever role that is, and so we’ll see,” Jayapal said, adding she is focused on the progressive caucus’ current work for now.

Jayapal and her liberal allies maintain that, even if more of their policy goals are stripped from the final legislation, they secured procedural wins along the way — such as hitching the social spending legislation to the infrastructure bill for most of the year. The left also advocated for a “trim-everything” strategy that involved more programs, but with shorter timelines, which Biden ultimately adopted.

Those tactics were worth the messy internal battles, as Jayapal sees it, if they help liberals preserve key pieces of the bill.

Other Democrats, however, insist party leaders would have never abandoned Biden’s broader social policy bill, even if the president did sign the bipartisan infrastructure bill earlier. And some progressives — such as the half-dozen who voted against the infrastructure bill just before Thanksgiving — don’t believe their caucus should have let the bills get decoupled soon as they were.

Yet perhaps most significantly for Jayapal’s caucus, activists who had forcefully pushed for more ambitious legislation are coming to recognize the limits of progressives’ power, now that the Senate holds the final say.

“Progressives can only control a slice of what happens in the entirety of the landscape of the federal government,” said Indivisible National Advocacy Director Mary Small.

Senior liberal Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) summed it up: “You got to know when to hold and know when to fold.”

Several of the half-dozen Democrats who voted against the infrastructure bill in November seem to share that sentiment, signaling this week they were likely to support the final version of the safety net legislation, if their other option is nothing.

“I don’t really see a world in which I vote against Build Back Better, because we need those investments,” said Rep. Cori Bush (D-Mo.).

And Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) reserved the right to make a final assessment, but underscored that there was “no scenario where I would vote against a transformative piece of legislation.”