Story and Photos by Matt Axling, Yellow Island Steward

I am a terrible swimmer. I sink straight to the bottom of the pool. I avoided swimming lessons my entire life. When I smell the chlorine at my son’s swim lessons, my palms sweat. With all of these factors, it is ironic that I have spent so much of my life on the water.

I am a mediocre biker. What I lack in talent I make up for with effort and silly biking socks. I really love biking to work. The morning commute has put me in a great state of mind as I arrived at various past jobs. And an uphill ride back to my house helps me leave my workday behind and be present for my family when I arrive home. I first started biking to work in Seattle in 1993 when I worked a summer job at a cherry processing factory in Georgetown. Nobody was riding their bikes around Seattle at the time. There were no bike lanes or established bike routes. My shortcuts included cutting through the Kingdome parking lot and the SoDo rail yard. I was hooked.

After accepting the position as steward for Yellow Island for The Nature Conservancy, my bike commuting has taken a back seat. In no way can I complain about my current work commute. I hop in the trusty Yellow Island boat in Friday Harbor, and zip out to Yellow Island in 25 minutes. Traffic consists of pods of orcas blocking my route and the only time I am forced to slow down is when the wind is blowing.

Yellow Island sits in San Juan Channel. 85% of the time, the weather is cooperative and the trip to Yellow is uneventful. The other 15% of the time, you don’t want to be on the water.

Orca cruises past the Yellow Island cabin that is occasional home to island steward Matt Axling.

Yellow Island cabin amidst the storm.

The Yellow Island boat was built in the late 1980s in Anacortes. It is a fiberglass landing craft that is good for hauling trash, tools, or people. It has dutifully sat in the water for close to 30 years as various caretakers have navigated their way to and from the island. The boat is powered by an 85hp Tohatsu outboard engine. The engine was purchased on the same day that I was hired four years ago. Since that time, I have put 300 hours of travel time on the engine.

The Yellow Island boat tied up on the shore.

I am very conscious about my boat usage and that 85hp engine has often given me pause. It is easy to see how a motorboat can have an adverse impact on the marine environment. Outboard boat engines are not known for their fuel efficiency. Also a boat traveling through the water at 20 knots and emitting a roar so loud that I wear ear protection are other factors which can impact marine mammals, birds and fish. At times, that engine has seemed incongruous with our mission.

May was Bike to Work Month. This was our second straight Bike to Work Month where we did not participate in bike to work due to COVID. So, in an effort to align my commute with TNC’s mission, to get a little exercise, and to have a spring project to focus on, I decided that May 2021 should be “Row to Work Month.”

THe Right boat

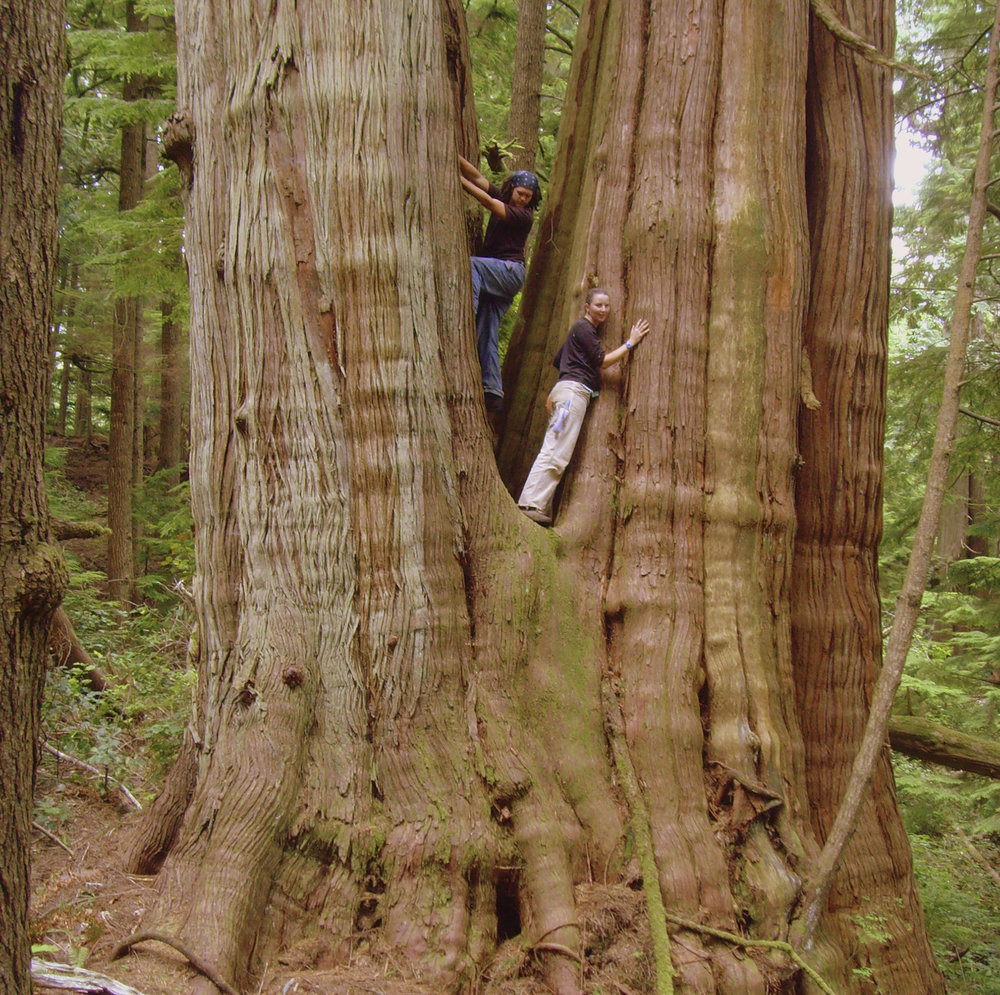

The waters around Yellow Island can be a little dicey. While San Juan Island offers some shelter to Yellow Island from the seasonal SW wind blowing in from the Straits of Juan de Fuca, the currents and wind dynamics of San Juan Channel can be tricky. Kayaking to Yellow Island is something that should only be done under perfect conditions, and if I was going to power myself to Yellow for an entire month, I was going to need a bigger boat.

My mother and uncle were kids who grew up in Ballard. Like most Norwegian immigrants, they have boating in their blood and various derelict boats in their driveways. My mom owns a 14-foot Whitehall rowboat built by Gig Harbor Boatworks. This model boat rows like a dream and is used as an open water rowboat by people traveling through the Inside Passage. The boat was rebuilt by my uncle a few years ago. I hadn’t seen either of them in over a year due to COVID. I scheduled my COVID shot for late April in their hometown as an excuse to go pick up the boat. As I was leaving with the boat in tow, my mom came running out of the house waving a small object and yelling “DON’T FORGET THE PLUG!!!!” I was off to a good start.

The 14-foot Whitehall rowboat at rest.

Fast forward to the end of May. I have now commuted the entire month out to Yellow using my rowboat. I have rowed about 44 miles during 5 round trips excursions to Yellow.

As I expected, I saw and experienced many beautiful and amazing things by slowing down. I rowed near a pod of orcas which seemed much bigger and waaaaay more intimidating than when I am in my motorboat. I hugged the shoreline and saw guillemots fledging for the first time. I picked up some marine debris which washed up on a rock during a winter storm. When I was hot, I hid in the shadows of San Juan Island, and when I was cold, I rowed in the sun in the middle of the channel. I laughed at my ridiculously slow progress when I was rowing against the current and enjoyed several exciting trips downwind.

Matt Axling at the oars.

Closeup visit with an orca.

You never know what you’ll find in the water, including this old tire.

Some days are barefoot days.

What I didn’t expect was how solo rowing for a month would connect me to so many people. Bike commuting has some similar parallels. Simply because you are not behind a windshield, you are forced to interact with everyone in your surroundings. You talk with all kinds of people. I noticed this when I was leading international bike trips in Argentina and Norway with groups of youth. Even though we didn’t share a similar language or culture, the bike would bring people together because it was a common experience.

At the Port of Friday Harbor, my little rowboat soon became a focal point for many people. I received a phone call from somebody who wanted to buy the boat on the spot. People were often gathered around it when I arrived in the morning or waved at me when I was rowing through the port. I soon became known as “the guy who was rowing to Yellow”.

lessons learned from a month of rowing

May is my busiest month of the year on Yellow. The flowers were out and people flock to Yellow to see the progression of blooms.

Indian paintbrush in bloom with the Whitehall rowboat floating in the distance.

Due to COVID protocols requiring me to keep my distance from the public, I spent much of the month talking with the public while sitting a safe distance away at my picnic table. With my rowboat tied up to the mooring ball behind me, eventually the conversation would turn to the boat.

“Are you rowing to Yellow? (yup)

“From where?” (Friday Harbor)

“How long does it take?” (Depends on wind and tide but about 1 ½ hrs)

“Aren’t you tired?” (Yes – but in a good way).

“Why are you rowing?”

It was this last question which sparked the most conversation. Yellow Island is indeed a special piece of land. It is unlike anything that exists in Washington and is truly unique. Its conservation value is important, but I think its true power is its ability to connect people to our work. People who come to Yellow aren’t just looking for flowers. They are looking for a connection to the land. The reason I was rowing to Yellow Island changed over the course of the month. What started out as a fun side project, turned into a deeper conversation about ways to do things differently. How the ways we have viewed stewardship, and people’s ability to access our lands needs to evolve and grow and to include more voices. Just like rowing the boat, sometimes we need to slow down and take the time to value the quality and depth of our work and relationships which we are trying to build.

As I write this, I have a few more rowing trips to complete this month. Visitation is quieting down and my busiest month of the year is coming to an end. Signs of summer are in the air: pregnant seals are returning to the island, spotted towhees are singing and the Island’s flowers are going to seed. Rowing back and forth has reminded me to look at our work from all different angles. If we listen and take our time, amazing experiences can be created.

Learn more about Yellow Island