President Biden signed the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act last week on a blustery afternoon in the other Washington. We’ve been digging into what this big, bipartisan infrastructure package means for this Washington since the bill was making its way through the Senate over the summer, and our staff and partners are busily planning for putting the incoming funding to good use on the ground – and in the water – for healthier, more resilient communities.

Now that it’s been signed into law, how might the infrastructure funding show up in your neighborhood?

President Biden addressed a bipartisan crowd of lawmakers and journalists before signing the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act on November 15.

A healthier Puget Sound, cleaner waters and help for salmon

The Environmental Protection Agency’s National Estuary Program protects and restores 28 estuaries around the country, including the Puget Sound and Columbia River Basin. The infrastructure bill includes $89 million for the Puget Sound Geographic Program and $79 million for the Columbia River Basin Geographic Program.

Rep. Derek Kilmer, whose district includes Washington’s Kitsap and Olympic Peninsulas, said that federal investments in recovering and restoring Puget Sound are critical to the environmental and economic future of our region.

>

“Having the federal government step up and help in this effort is absolutely vital if we’re going to recover our salmon populations, ensure future generations can dig for clams, and respect tribal treaty rights. As Chair of the Puget Sound Recovery Caucus, I’m proud this bill will help advance a number of initiatives I’ve fought for to restore the Sound – which is important to our environment, to local jobs, and to our local economy.”

Senator Cantwell and Rep. Kilmer led the effort to create the National Culvert Removal, Replacement and Restoration Grant Program, included and funded at $1 billion in the infrastructure bill to help transportation agencies fix fish passage barriers that impact salmon. This is an especially big deal for Washington state, where addressing the culvert issue and improving salmon habitat are urgent needs. A bipartisan group of Pacific Northwest members supported the creation of this new program to help recover salmon in our region.

Coho salmon swim in the Sol Duc River. Photo by Adam Baus.

The bill also includes $172 million for NOAA’s Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund for states and Tribes to protect, conserve, and restore salmon.

More climate-resilient communities and ecosystems

Healthier estuaries and other ecosystems are more resilient to climate-change-related extreme weather events like floods, king tides, drought and wildfire. In addition to the benefits to people that come with cleaner water and the better functioning ecosystems covered above, the bill includes $491 million for Habitat Restoration and Community Resilience Grants and $492 million for the National Ocean and Coastal Security Fund Grants, according to Sen. Cantwell’s office.

Cape Flattery is part of the traditional homelands of the Makah Tribe. Tribes along Washington’s coast are on the front lines of climate change, with some actively relocating parts of their communities to escape sea level rise and storm surges. Photo by Elise Eliot.

AN Even bigger Deal for climate is on the way

The Build Back Better Act passed the House of Representatives just a few days after President Biden signed the Infrastructure package into law. Learn more about Build Back Better and its $555 billion in climate investments as the bill heads to the Senate for consideration.

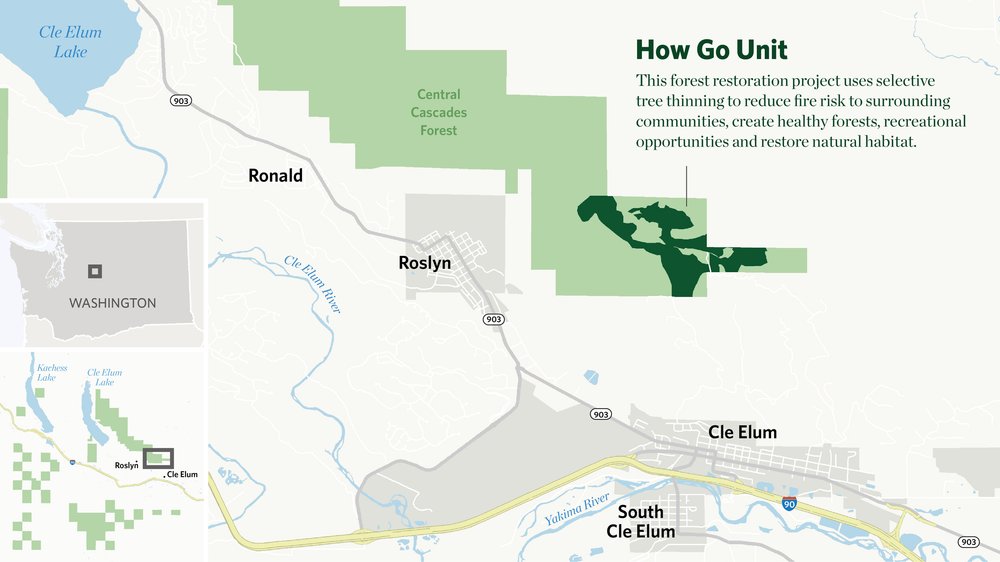

Also included is nearly $7.5 billion in investments for agencies including the USDA Forest Service and Department of Interior to help Washington and other fire-prone states prepare for and become more resilient to wildfires, including several new funding programs to accelerate forest restoration, improve watershed conditions, implement prescribed fire, and increase reforestation. Thanks to Rep. Kim Schrier’s leadership, the bill funds the Legacy Roads and Trails Program at $250 million, a big boost for maintaining and decommissioning roads to improve watershed health.

Cleaner air and more transportation options

The infrastructure law includes $1.79 billion in funding for public transit in Washington, expanding your options for cleaner, more energy efficient ways to get where you need to go.

Thoughtful transportation investments in transit and other alternatives to single-occupant vehicle driving, and innovative stormwater solutions like the bioswale under the Aurora Bridge, can be a game-changer for human health and salmon recovery. Photo by Courtney Baxter.

cleaning up Washington’s transportation sector

There’s still a lot of work to do on transportation in Washington state as we look for cleaner, healthier ways to get around and protecting our air, water and habitat in a growing region. With funding from the 2021 Climate Commitment Act designated for carbon emissions reduction and no time to waste to recover our iconic salmon, we’ll be advocating for smart transportation policy in this Washington during the upcoming 2022 legislative session.

You may remember, from the multi-year effort to join our West Coast neighbors and enact a Clean Fuel Standard, that transportation is the most significant source of climate-changing emissions in our state. We expect more than $70 million in infrastructure funding to go toward expanding the electric vehicle charging network in Washington, and billions more to go into grant programs like the Low-No Emission Grant program, which supports projects like electrifying municipal bus fleets (like King County Metro’s), and the Capital Investment Grant program, which funds other low- and no-emissions transit projects like the Link Light Rail. All of this adds up to more options for cleaner ways to get around and less polluted, more breathable air.

Speaker Pelosi addresses the crowd and television viewers before the signing ceremony for the infrastructure bill.

What’s next?

As big as the infrastructure bill is, the climate crisis is bigger: there’s still a lot more we need to do to ensure a livable future for generations to come – and a lot more we can do at the national level. That’s why we’re continuing to advocate for Build Back Better as it awaits consideration in the Senate, which includes even more substantial investments in addressing and adapting to climate change.

Learn more about Build Back Better

Banner photo by Morgan Heim.